For those of us who didn't go to culinary school, culinary knowledge is gleaned here and there: we skim recipes, watch chefs on TV, get tips from blogs (hopefully), and, more importantly, learn from the people around us. In this way, our culinary skills reflect our histories of love and loss, good times and dark times; the times we lived high on the hog, and the lean times. For example, I rarely eat a grilled cheese sandwich without thinking of my mother (who made them for me on rainy days) or my first serious boyfriend, Mark, who was a master and taught me the tricks of the trade (good thing too, since we subsisted largely on cheese and starch in those days): butter the bread before you throw it in the pan, cook at medium heat, use plenty of cheese, turn down to low, and cover until the cheese melts. Home baked bread is Julie Daniel (who set a standard I have still not reached) and Mary Lou Goertzen (who took me under her wing and taught me how to bake bread when I was eight or nine). Eggs Benedict is my friend "princess" Abigail and my husband, to whom she passed her secrets. Stuffed jalapeños are Greta Dahling. And so on... Food connects us to our past, to our heritage, to the people we love. And so, without further ado, a vital yet unsung culinary strategy from my friend Samuel Ferris Harmon, master of breakfast. I certainly never eat scrambled eggs without thinking of Sam, and here's why: he makes the brightest, fluffiest scrambled eggs you've ever seen. Sam taught me two key tricks years ago (make sure you whip the eggs thoroughly before throwing them in the pan and don't add anything because it tends to mess with the texture and color), but I asked him for additional details for this post. Sam's Perfect Scrambled Eggs (in Sam's words) Step One: Heat a non-stick pan to medium high heat (6 or 7). Step Two: Crack the eggs into a bowl and beat them with a fork or whisk briskly until they start bubbling. Step Three: Make sure that the pan is hot and put a generous amount of butter in the pan. Make sure to keep it moving and that the pan isn't so hot that the butter burns. Next, pour the eggs over the butter. Step Four: Gently fold the eggs with a spatula into the center of the pan until done. When they are done is personal preference. I like them cooked all the way through, but some people like them a little bit runny. Don't use any salt until the eggs are served--I've found that putting salt in before you cook them tends to make them dry out. Most of my favorite cooks belong to my parents’ generation. It makes sense---even if you do go to culinary school, learning to cook is a trial-and-error process, and so of course older cooks are going to have more impressive arsenals of tricks. Rachel Mercer, who is around my age, is an exception to this rule. Not only is she a creative, knowledgeable cook, but she has a culinary philosophy that rings true with me. She has an appreciation for and knowledge of fine ingredients, but she’s not a snob. She has an incredible depth of knowledge about the wine industry, but she’s doesn’t necessarily equate good with expensive. When Rachel comes to visit, she always brings interesting food or wine—a batch of freshly made scones, a platter of obscure and wondrous cheeses, ingredients for stir fry, or an excellent cava (make that several bottles—I don’t think Rachel has ever arrived on my door step without several bottles of wine). I’m making it sound as though I just like Rachel because she brings me stuff, but I’m trying to get at something deeper—I see food as a kind of communion. Consuming (and appreciating) truly delicious food and drink with friends and potential friends is my way of celebrating being alive. Rachel, with her culinary adventurism and generosity, makes that happen. When she’s not busy catering, pontificating on wine, teaching wine and cheese classes, baking bread for a local tasting room in Eastern Washington, making cool jewelry, or getting in ongoing arguments about history with her friends (ahem), Rachel works on her nascent business: raising sheep and making artisan cheeses. In the following interview, she shares cooking secrets and talks about her master plans. When did you start cooking and why? I don't remember. When I was a kid--and I mean perhaps as young as four--I'd play restaurant with my parents. If they were gone I'd set up a menu for them, and set the table. It was always a set menu (and probably something along the lines of hot dogs and grilled cheese). I was really young when I started doing that; so I know that my mother let me use the stove at a very young age. I also was a very, very picky eater as a child. As I grew up, I figured out that I'm a super-taster (thanks biology class!), so that might have had something to do with being picky? I could taste things really well...also had a keen sense of smell. Regardless, I was picky (ironic since I'm not picky now) and my mother's attitude was "you don't eat it, fix something yourself". We were not a family of TV dinners or even a microwave for a large part of my early childhood. Therefore, 'fixing' something usually meant that it did need to be cooked. Did someone teach you how to cook? My mom. But I don't recall 'cooking lessons'. I'd watch and duplicate, later. My mom is an amazing cook, it should be noted. We lived in the middle of nowhere, miles from any city, and I grew up eating stir-fry and curries. Which is somewhat typical these days, but this was atypical when I was growing up. Most kids had no idea what a wok was, let alone vindaloo. My parents had been part of the beatnik house boat generation in Seattle and had learned to cook 'exotic food' with their crazy friends. My mother took those skills back to the desert and could whip up amazing dishes. The biggest lesson I learned from her (whether this was taught or just learned by watching) was the ability to really understand flavors. Because of the distance to town, if we were short on an ingredient (or more often the case--no access to the exotic ingredient in the first place) she knew something to substitute. Always. Still does. Who or what has influenced your cooking the most? Hard to say, but I think where I live. I've noticed changes in my cooking styles as well as in my food, depending on where I live. And with each move I've become a better cook, thanks to these influences. I think because I grew up watching a great cook (my mom), I can't help but watch other cooks and seek them out no matter where I live. The two key places being Singapore and Austin. In Singapore I learned A LOT for lots of reasons...but it's a city of really good street food. And all kinds: Chinese, Indian, Malay, Thai. In Austin, I was working and living around brilliant chefs (executive chefs who graduated top of their classes at NY and London Cordon Bleu). We all threw elaborate house parties, and it was always a comforting environment. Austin's a southern foodie town. People are really into food (whether it's barbecue or classically trained French cooking), but it's the south. They're really excited about food, any food, and want to share the food and the knowledge of how to cook the food with everyone and anyone. There's little of that snootiness that I've seen in other food towns. Can you tell me a little about your professional history with foods and beverages? When I moved to Singapore, I ended up getting various jobs, including cooking for a family. They paid me a ridiculous amount of money to cook for them. I wasn't making anything fancy, but they missed 'American' cooking, and I could make food that the kids actually liked to eat (even the vegetables). I liked that job. A lot. It also amazed me that someone would PAY me to cook for them. What a concept. It took me a few years to actively seek out more work in this industry. I ended up working for a winery in Wenatchee, WA. My parents had a winery in the early, active, years of the WA state wine industry. (The industry goes back to the late 1800s here, but it took about a century for a real wine culture to develop.) I knew wine, liked wine, but also knew it to be heart-breaking industry so I had avoided it until that point. Since then I've had various jobs in the food and beverage business. Worked for a few other wineries (everything from winery management to just harvesting grapes and working crush), managed a wine bar in a grocery store (best idea...who doesn't want to shop with a glass of wine?), and now I'm trying to do more with cooking--I'm the summer cook for a local winery while working with a friend catering. What is your favorite dish to cook? I don't think I have 'a dish' but more of a genre. I love cooking soups for people; they're comfort food, tend to be really forgiving (so if you forget something, add too much of something else, want to chat with your guest more...), and a lot of people don't love soup the way my family does. There are a lot of really horrible soups out there, and I usually never order soup when eating out (unless, of course it's pho or Korean or laksa), because I'm more disappointed than not. But that's why I like to make soup. I make really good soup, and I like to surprise people with how good soups are. I often force them on entire groups of unsuspecting patrons. Can you share some favorite strategies or culinary secrets? Boil firm tofu. In fact, boil the hell out of it; then stir-fry it or add it to your soups, etc. What are your favorite tools or pieces of equipment? Cast iron skillet & dutch oven. The non-enamel kind. I don't know how many one-pot dishes I've made in my trusty skillet--and you can take it camping with you or use it as a weapon. When you feel a dish needs a little something extra, what are your go to spices/ingredients? Fish sauce. I put it in everything--it's salty and savory and very useful outside of Asian dishes. But I also love spice--so a dash or 5 of chili sauce/powder is nice. I also find myself stuck on certain specific herbs. Right now? Cardamom and thyme. At one point I'm fairly certain I was addicted to nutmeg (it's great on roasted chicken thighs!). Any culinary pet peeves? Food snobs. Oh, and fucking prime rib. Everyone wants prime rib when you're catering a meal. It's not THAT good and it's freaking expensive....when I could do a barbecue braised brisket, or slow roast a cheaper cut of roast in a thick sauce of wine and onions--that'd taste better as a catered meal (prime rib is often cold by the time it's served to everyone), and save you that cash. If I have to cook one more prime rib and salmon meal... Any words of wisdom on the wine front? Nothing specific....but it's in our (the consumers) favor right now. There's a lot of wine out there; too much wine. I suspect there will be a fairly major shift in the industry in the next four years...The consumer probably won't notice it a whole lot besides more affordable wines. And as a rule, don't listen to wine critics--besides me. Oh, and if you've lost your taste for white wine--start working on developing it again. That'll be the new trend, and I'm excited for good, interesting white wines to take the spotlight. Making white wine is a lot more difficult than making red wine, and it's time that good white wine makers got their moment in the sun. Any interesting wine/food discoveries/obsessions of late? I just went to Taste Washington in Seattle and there were a fair number of hard cider producers there--most of them really good. One cider house made a champagne style cider (with champagne yeast) that I loved-- www.finnriver.com . What are your culinary/business goals? I have more than a few. But the two biggest ones are to complete a vegetarian/carnivore comic adventure story cookbook that I've started with my vegetarian friend, Michele, and to make farmstead cheese (with milk from my sheep). What is your most indispensable ingredient? Salt and pepper. Probably why I love fish sauce so much (it's salty). But I don't know how many times I've thought "this dish needs something extra" and before I start adding in exotic curries or smoked paprika or Tapatio...I just salt and pepper the dish and--bingo. That's it. I think that because we've had this (much needed) foodie revolution in America we forget how to use more traditional spices. Less is more, often. If you could cook dinner for one person living or dead, who would it be? And why? Oh man....I can think of a bunch of dead people I'd love to cook for (Thomas Jefferson being a the front of that list) but...I have a hard time with these kinds of questions. Because, let's face it. It's completely theoretical, yet I can't help but think about it as if it'd really happen. I'm female and a cook...so I get to cook for some famous dead guy. That'd be the end of the story. In ye olden days cooks were not praised for their food--the master of the house was praised for the food. Not that I’d like to be praised, so much as sit down and break bread with him...But that wouldn't happen. So a living person I'd like to cook for? Anthony Bourdain because I may or may not have had a crush on him for the past 12 or so years and I love how he loves food...and drinks. I think we'd have fun drinking together, if not stuffing our faces while we're at it. You can read some of Rachel's recipes here. The first post in the soon-to-be-ongoing series on the cooks in my life, past and present.

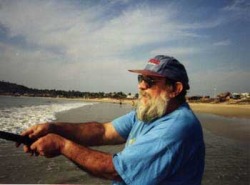

It seems appropriate to start this series with the first cook, or rather the first cook who influenced me, my dad, Stephen Hale Rogers. Even though he was famous for his cooking (somewhat literally) and conjured some of the best food I have ever eaten, I never think of Steve as a chef---always as a cook. Anything but a snob, my dad cooked the way your grandmother might cook if she happened to be capable of shifting ethnicity several times a day and had a predilection for undermined ingredients (fish heads, jack, government cheese). He cooked comfort food in that his dishes were often saucy, usually fatty, and always intended (perhaps required) to be eaten in large quantities. He was not the sort of man who blinked an eye if six extra people randomly showed up at dinner time. His comfort food was comforting because the cooking of it infused the house with aromas and warmth, and the eating of it always entailed the camaraderie of satisfying gluttony. It was not, however, bland or easy. I think growing up in Ohio in the 1940's gave my dad a disdain for many types of meals that perfectly acceptable to the foodies of today. Roasted chicken, mac n' cheese, meatloaf, pot roast, steak--these things were never served in our house. As a 14-year-old, my dad had rebelled against his mother's Midwestern cooking and started on his culinary career. The first dish he served his family was fish head soup, and that was portentous of things to come. He thought breakfast foods were boring, but wasn't one to pass up on a meal, so breakfast at our house (at dawn, before I left on the long bus ride to school) consisted of enchiladas verde, giant fried burritos, or possibly 'a nice curry' sold in a wheedling tone to a blurry-eyed ten-year-old who dreamed of Cinnamon Toast Crunch. His appetite was limitless, and his curiosity was boundless. He cooked everything from chimichangas to African groundnut stew. He ate songbirds in Thailand, Armadillo in the Yucatan, Iguana in Oaxaca. Being a cheapskate and a culinary explorer, he dismissed restaurants, preferring to ferret out the grungiest (aka most 'authentic') street cart in the most dubious part of town. He called this practice 'street grunting', with a gleam in his eye. When I turned 19, my friends and I drove up to Vancouver to celebrate. I called my dad to tell him about our adventures. "Vancouver!" he cried, "a great city for food. There's fantastic Asian food in Vancouver, especially if you get out of the tourist districts. Where did you go?" I was obliged to tell him that we'd gone to a Hooters (it wasn't my idea, I protested) where I'd ordered a grilled cheese sandwich. His mournful, disappointed reproach still rings in my ears. My dad didn't teach me to cook, because that would have required him to actually let someone else into his kitchen. But I think I learned a lot by osmosis, sitting on a stool, my elbows on the kitchen counter, watching the mad, joyful flurry that was his evening ritual. Perhaps more importantly, I learned that food was a way to bring people together, and that all was right in the world when a circle of people sat around a table bellowing things like "Pass the ground nut stew!" and "Is there any more of that habanero stuffed squid?" You can read my dad's recipe for Chiles Rellenos here. |

Consumption

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed