I’ve imagined this moment before. Like the way it crosses your mind that your dad or favorite uncle is going to die eventually. But in my mind, when John Prine died, we’d have a vigil in some appropriate spot. Maybe on the banks of a summer river or on a front porch or on a Mexican beach with tequila and guitars and a handful of the best people. We’d build a fire and pass the bottle and share stories and gain some modicum of comfort out of a sad goodbye.

I did not imagine that I’d be alone in a cold house with no hope of company other than a computer screen. Grieving is a strange thing in the time of Covid-19. I’m writing in place of the real communion I’d wish for us all. At least I have the bottle of tequila.

My dad, Steve Rogers, was a big bear-like man with a Jerry Garcia beard and a twinkle in his eye. A marine biologist turned vagabond, he was sweet-natured but he had acerbic opinions, one of which was that most music written after 1965 was an awful racket. He made an exception for John Prine.

As a kid, I didn’t think it was cool to like my dad’s music. But John Prine spoke to me. He seemed like someone we would know. Someone a bit eccentric, but also totally down-to-earth. Someone who would be sitting on our front porch, shooting the shit, but saying everything just a little better than we could. He was a smart weirdo with a keen eye for the details that elevate life into art. Or maybe it’s the other way around.

My first real concert was John Prine with my dad when I was maybe 16. At the time, I was trying to figure out my place in the world. I’d tried preppy and failed. I was trying tough and it was better. I was doing okay with petty vandalism and wearing maroon lipstick and acting like I hated everything. But I couldn’t hate my dad. I was excited to go to the show and hoping that John Prine would play my dad’s favorite, “Paradise.”

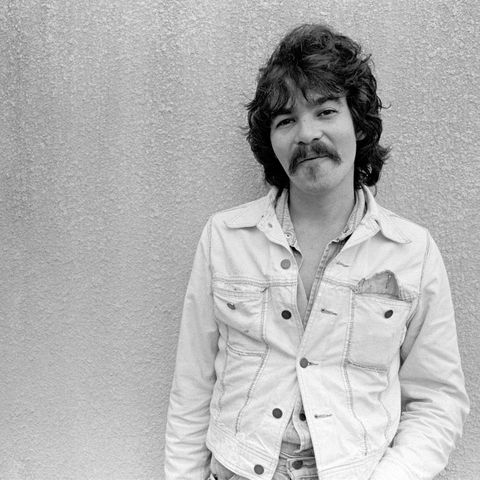

John was playing at a sit-down opera house, and I was expecting the show to be serious and formal. It was anything but. With his friendly paunch and rakish mustache and mischievous twinkle, John Prine led a rousing chorus of “That’s the Way the World Goes ‘Round.” Staring around a hall full of happy people raising their beers to the roof, it occurred to me that this song was edgier and smarter than any of the dark bands my friends liked. It acknowledged the essential terribleness of life, while at the same time offering wise comfort:

That’s the way the world goes round…

Your up one day, the next your down…

It’s a half an inch of water and you think you’re gonna drown

That’s the way the world goes round…

I’d been looking for my place in the world. I’d thought maybe I could be a preppy or a skater or a goth, but instead I’d found my place amongst a bunch of tipsy people who looked like bird watchers and high school librarians. Somehow, I was fine with that.

Three years later, I bought tickets to a show on the banks of the Willamette River, outside Portland, Oregon. My dad had been diagnosed with cancer of the bile duct. The doctors said he had six months. I barely had enough money for the tickets, but I thought the show could be our last big trip together, like something from a movie.

But when the day rolled around, Steve was too sick to go. By that time, his skin had turned yellow and he could barely get up. I went to the show with my friend Chelsea and her mom, Kathy. We were too young to get into the beer garden, so we shoved a few beers into the waistbands of our jeans and wore baggy shirts, Kathy included.

While drinking Corona on the lawn, we were accosted by an officious security guard who demanded to see our identification. Kathy was the hot mom type, so I wasn’t totally surprised when the guard asked for her ID as well, but I was slightly more surprised when she seemed to think it was a fake. We were made to dump our beer out and relinquish the beers from our pants, but it was still one of the best shows I’ve ever seen, and my only happy memory of that time. The sun glittered silver on the river as John Prine sang “Lake Marie.” Do you know what blood looks like in black and white video? Shadows…

In the end, Steve only lived six weeks after his initial diagnosis. He died on July 1, 1999. His old friends played “Paradise” at his funeral. My mom and I did our best to carry on as usual, and two weeks later we went to The Oregon Country Fair, an annual hippie “family” reunion near our home. It was disorienting to be around so many happy people. I struggled to relate in the usual ways. I was feeling a distinct disconnect from reality.

Late one night, I was wondering through the woods when I came across a group of musicians playing in the dark. I could barely see them—they looked like bearded dwarves silhouetted against the tree shadows. (Okay, I was high.) As I approached, they struck up a rousing rendition of “Paradise,” jug band style. It was like flicking the switch that reminded me this darkness and sorrow had always been with us, was not unique to me, and could not extinguish the deep currents of joy.

My dad had a rare sensibility—at times cynical yet also deeply sentimental. He could see the darkness, but he had a great love for people. When I missed his commentary and his delight in strange details, I’d put on a record and find that same spirit in Prine’s voice.

As I grew older, I carried my records with me and John Prine came to remind me of a lot of people and times—both good and bad. I tried to go see John play once or twice a year, and hearing him talk always brought me home. I even once wrote him a letter, which I never sent. I wanted t tell him “That’s the Way the World Goes Round” had saved me from myself in my darkest moments. I wanted to thank him for getting me through so many sad times and for so eloquently acknowledging the darkness and the beauty of the world—and usually with a chuckle and a wink.

My memories may be unique, but they are not singular. If you love John Prine, you have a story about a wedding, or a breakup, or a funeral, or a lost friend, or a perfect day. Probably all of the above and then some. His songs are part of who we are—And unlike memories, they never wear out.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed