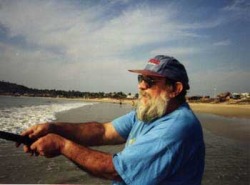

It seems appropriate to start this series with the first cook, or rather the first cook who influenced me, my dad, Stephen Hale Rogers.

Even though he was famous for his cooking (somewhat literally) and conjured some of the best food I have ever eaten, I never think of Steve as a chef---always as a cook. Anything but a snob, my dad cooked the way your grandmother might cook if she happened to be capable of shifting ethnicity several times a day and had a predilection for undermined ingredients (fish heads, jack, government cheese).

He cooked comfort food in that his dishes were often saucy, usually fatty, and always intended (perhaps required) to be eaten in large quantities. He was not the sort of man who blinked an eye if six extra people randomly showed up at dinner time. His comfort food was comforting because the cooking of it infused the house with aromas and warmth, and the eating of it always entailed the camaraderie of satisfying gluttony. It was not, however, bland or easy.

I think growing up in Ohio in the 1940's gave my dad a disdain for many types of meals that perfectly acceptable to the foodies of today. Roasted chicken, mac n' cheese, meatloaf, pot roast, steak--these things were never served in our house. As a 14-year-old, my dad had rebelled against his mother's Midwestern cooking and started on his culinary career. The first dish he served his family was fish head soup, and that was portentous of things to come.

He thought breakfast foods were boring, but wasn't one to pass up on a meal, so breakfast at our house (at dawn, before I left on the long bus ride to school) consisted of enchiladas verde, giant fried burritos, or possibly 'a nice curry' sold in a wheedling tone to a blurry-eyed ten-year-old who dreamed of Cinnamon Toast Crunch.

His appetite was limitless, and his curiosity was boundless. He cooked everything from chimichangas to African groundnut stew. He ate songbirds in Thailand, Armadillo in the Yucatan, Iguana in Oaxaca. Being a cheapskate and a culinary explorer, he dismissed restaurants, preferring to ferret out the grungiest (aka most 'authentic') street cart in the most dubious part of town.

He called this practice 'street grunting', with a gleam in his eye.

When I turned 19, my friends and I drove up to Vancouver to celebrate. I called my dad to tell him about our adventures. "Vancouver!" he cried, "a great city for food. There's fantastic Asian food in Vancouver, especially if you get out of the tourist districts. Where did you go?" I was obliged to tell him that we'd gone to a Hooters (it wasn't my idea, I protested) where I'd ordered a grilled cheese sandwich. His mournful, disappointed reproach still rings in my ears.

My dad didn't teach me to cook, because that would have required him to actually let someone else into his kitchen. But I think I learned a lot by osmosis, sitting on a stool, my elbows on the kitchen counter, watching the mad, joyful flurry that was his evening ritual. Perhaps more importantly, I learned that food was a way to bring people together, and that all was right in the world when a circle of people sat around a table bellowing things like "Pass the ground nut stew!" and "Is there any more of that habanero stuffed squid?"

You can read my dad's recipe for Chiles Rellenos here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed